With her new christening as Pamela and brightly varnished teak, and my restless hands hands longing to trim her sheets, it was time to take my cutter-rigged Crealock 37 on my first single-handed ocean sea trial, an overnight sail from San Francisco bay through the Golden Gate to desolate Drakes Bay on the beautiful Point Reyes peninsula. Drakes Bay seemed like a good challenge, especially for me single-handing. There is something ominous about taking a boat outside the protected waters of the bay and into the rollicking Pacific rollers along a rocky lee shore. Often foggy, the cape of Point Reyes has claimed literally hundreds of ships in the past 400 years of nautical history. The Gate is more than a portal from the world’s most lovely city to the blue ocean beyond; it is a milestone in the life of a sailor. Turn left and you fly downwind and surf the rising swells. Turn right and you take them hard on the bow while you battle the 20-knot winds head on. Go straight and you sail into the sunset and on to Hawaii, beam-reaching your way to the trade winds that enabled the Age of Discovery.

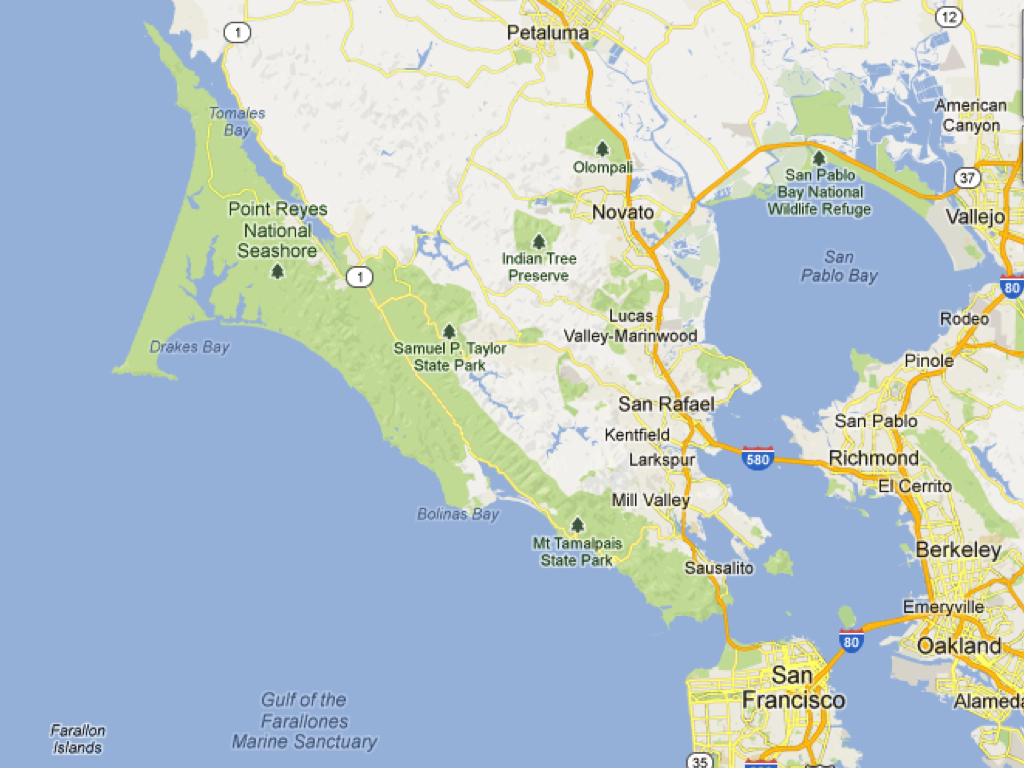

Drakes Bay lies about 30 miles past the Golden Gate, or about 40 nautical miles when tacking against the prevailing north-westerlies. It is a protected anchorage in typical conditions, but must be avoided when the winds clock to the south to announce the coming of a winter storm.

Point Reyes is a triangle jutting out from the California mainland, and is believed to have moved up from Southern California millions of years ago. It is part of the Pacific tectonic plate under the great ocean, totally separate from the North American plate which forms the mainland. It is separated from the mainland by the San Andreas fault, which forms the beautiful Olema valley from Tomales Bay on the northern end to Bolinas Bay south. On its southern end begins a graceful curve to the west ending in a dramatic rocky cape a few miles out to sea.

I found myself approaching this cape in complete darkness and thick fog and screaming along at 6 knots.

The day had been sunny with great visibility and was expected to reach 70 degrees in San Francisco, unusual for early March. It was a Monday morning and very few boats were out. Everyone else was trying to get to work. I passed under them on the Bay Bridge. While they stalled in their cars Pamela caught a light northerly and picked up her bows in anticipation of a great adventure brewing. She sailed easily along the city front and pointed to the Golden Gate and the sea beyond. How happy I was! Single-handing my own sailboat on a gorgeous Spring morning, light winds on a close reach, catching a strong 4-knot ebb tide to sweep me through the Golden Gate. And to adventure!

The seas beyond the Gate were very gentle. A swell began as soon I passed the Golden Gate Bridge, but ever so mild, one to two feet. I brought my guitar up on deck and sang my ocean song. I delighted in the warm sunlight.

The seas picked up a bit as I moved out beyond Point Bonita. It was time to put the guitar away. I was apprehensive about getting sea sick, as I had once done off of Point Bonita. It was a sailboat race to Drakes Bay several years ago with my buddy Bill and his little ship Zora. For several months I had been pressuring Bill to take Zora out into the ocean, and he gradually agreed, although without great enthusiasm, and registered for the Drakes Bay Race sponsored by the Corinthian Yacht Club. On that morning I glanced through the binoculars at the Point Bonita lighthouse just as the swells were beginning, when suddenly my stomach gave a lurch and I knew I would soon be sick. A short while later I was nearly lifeless, sitting limp in the cockpit and not moving — not joking, not laughing, not helping sail the boat, and not preparing lunch. And what a lunch I had planned! For weeks leading up to the race I had planned what wonderful food I would prepare for the crew. Yet there I was, unable to get up and go down into the galley to make anything while the crew sat hungry as the day wore on. All my talk about sailing across the Pacific! What complete crap — here I was absolutely immobile about a mile into the ocean. One can plan, one can boast, read all the literature there is about the sea, and wax poetic about the ways of the sea; and in a single instant be claimed by the sea.

Now some would believe that this very point proves that planning, boasting, reading, and waxing are ridiculous. The sea will eventually get you, so stop all this baloney. Take care, be serious, put down the guitar and stop singing such naive songs about Mother Ocean. I say the opposite: since the sea is going to get you, you had best plan, prepare, read, and sing as many naive songs as you can in your life time.

On that day with Bill and Zora, I up-chucked my breakfast into the sea, moped about for a few hours feeling like a foolish boy, and then staggered to my feet and announced that I would make lunch or die in the attempt. The crew ate well after all.

The memory of that day so many years before brought a twinge of anxiety as the swells began to build. I didn’t think I would get sick this time, and if I did, oh well — in the words of Joshua Slocum, the first solo circumnavigator, “What of that?”

I heard a sudden gasp of air. From the blowhole of a mammal in the water — a whale? Something black out of the corner of my eye was buried quickly into the sea. I looked around and saw nothing. A half a minute later I heard it again, this time off the stern to starboard. It was a dolphin. A black dolphin, following me along outside the Golden Gate. He followed me a mile or so and I was happy to see him surface each time, until he surfaced no more.

I spied the bluffs of Drakes Bay 30 miles away. At first it looked like an island, for the plain leading to the cape looks rather low from that angle, especially as the Marin headlands loom in the foreground. I don’t recall an island formation like the Farallones just north of the Farallones, but sometimes you learn of something like this, like the fact that there is an island 27 miles off the coast of California beyond the Golden Gate. And when you first hear of it, you think, “Oh, interesting. I suppose there could be an island off the coast.” And so maybe there actually were islands beyond the Farallones. I checked my chart two or three times to make sure there was no such island.

When you first see your destination on a long backpacking trip, you think it is something else, something far distant. You find hills or ranges between you and the destination and you imagine that they are the destination, and the false destination is actually something way further off, miles farther. When you think you have reached the top of a ridge or a mountain, you find that you have reached just a shoulder. And onward is the summit. And you gulp.

So it was with Drakes Bay. The island so far off was Drakes Bay, and it seem a hell of long way off, and the wind was coming straight from that direction and was picking up a bit. Some fog was forming in a bank a little way off from the cape.

Pamela made steady progress past the most spectacular coastal scenery in all of California. I tacked toward land and sailed in close to the shore to see the sheer bluffs and sea caves. The forests of Marin are untouched and have some of the very oldest of trees, the Muir Redwoods. When I could clearly make out the surf line and see the pounding waves on the rocks, I watched for a bit then tacked to seaward.

“All hands, prepare to come about! Ready about?”

“Ready on port.”

“Ready starboard.”

“Helm’s alee!”

What an adventure it is to tack a boat by yourself. You never have to wait for someone to say, “Ready”, nor remind crew to call forth with such responses to issued commands. You simply shout, “Ready!”, or perhaps you feel like a bugger and you delay shouting Ready just to see if the skipper will get pissed at you. And you turn the helm and let go the working jib sheet and grab the lazy sheet to take in slack, and pull hard around the winch, and check-swing the helm to stabilize the turn, then switch back on the autopilot while heaving the sheet one last time before resorting to grinding. All in 30 seconds and without losing two knots.

On the seaward tack I could see the Farallones. Only fifteen miles off, they seemed small and distant. The seaward tack was the slow tack, doing only about 4 knots. The seas were building to white caps and were hitting harder on the starboard bow on the seaward tack. The shore bound tack was faster and more comfortable, easily 6 knots. It was glorious sailing.

A moon came rising in the eastern sky, prematurely it seemed. Meanwhile the sun began to settle its day-long flight. Any moon flying over any sea is utopia, and all sunsets added together make nirvana. This sunset melted softly into the fog bank offshore and invited me to follow. Not yet. That’s coming. Be patient.

I was hoping for a bit more sun before ending this day, as I had another hour to go before reaching Drakes Bay. Happy to have a full moon, though. Not long after the sunset the fog moved in and obscured the cape. In a short while it was completely dark and with near-zero visibility. The moon was still there, and to seaward a few stars shining brightly enough to pierce the fog bank.

I thought of Pam. I wanted her there with me but she would have freaked out with the waves, darkness, and fog. She has yet to learn to use Pamela’s instruments and to trust that they will guide you safely into the anchorage. The radar showed the cape and some obstruction on the north west part of the bay, while the chart showed water depth and the AIS (Automatic Identification System) indicated whether there were any commercial boats, like fisherman, out and about or anchored in the bay. I was pretty sure there were no other sailboats about. No one is crazy enough to go to Drakes Bay for no reason.

Nothing on the seven seas works quite as well as Pamela’s windlass, a sturdy bronze Muir. We plopped down the 45-pounder in 28 feet of water and let out 150 feet of chain. She wavered not a bit after that, but was happy to bed down for the night. The chart plotter showed how far I was from the beach, and as I rose to check it four times during the night it always showed about 890 feet to the closest depth line.

That night and the following night were spent listening to all the mysterious sounds about the ship, especially the rigging tossed by the whistling winds. Periodically I would rouse myself from my light sleep, don my foulies and clamber up on deck to see what I could do about lines whacking on the mast. I tied a web of preventers, knots, and bungies from the various halyards and sheets to the spreaders and stays, but there would always remain a single mystery line a-whacking away. Standing at the mast in a light gale I struggled to perceive the mystery line; when I returned to my bunk it would start up again, bright and true. It had a mind of its own, and a song to sing; who am I to attempt to control it? I’d best enjoy the song.

At last I would fall into deep sleep, as is inevitable even in a sleep-deprived environment. In deep REM sleep I had dreams, including nightmares about falling overboard. In one such dream I found myself in the water behind the boat. Jib sheets were streaming in the breeze aft of the boat but I was unable to reach them. Pam was on deck, and she was in a fair panic. She did not know what to do. I yelled, “Turn around and get me!” while off she and Pamela sailed.

In another dream I found myself in mid-air above the cockpit. You have a feeling of complete weightlessness when you are thrown into the air, as on a trampoline. I felt myself in this state, moving upward, and was immediately cognizant that I’d been thrown high into the air from some amazing violent force against the ship and was still flying higher as Pamela sailed on. The feeling in the dream was incredibly real. At once I knew my fate. I thought to myself, “This is it! This is actually The End!” I imagined myself sinking into the deep while I was still high in the air. This dream seemed completely final, the dream to end all dreams. And yet dreams, like al things, must come to an end.

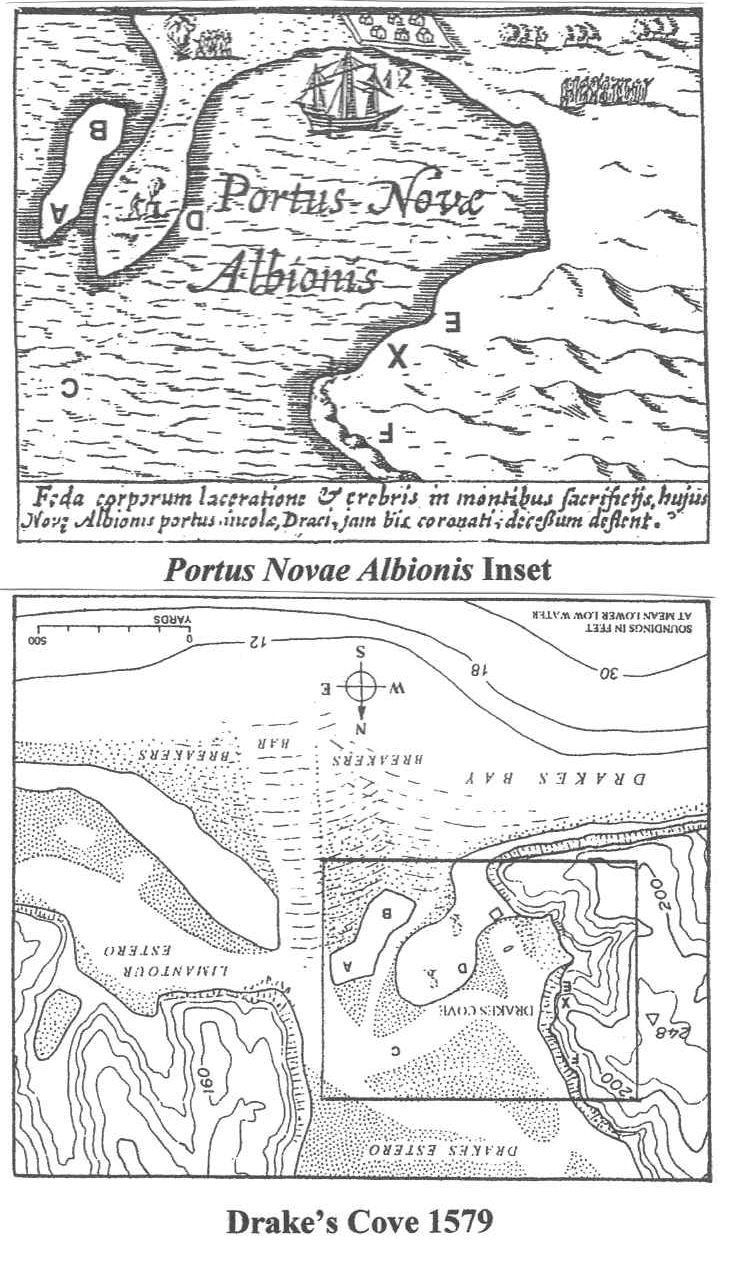

Sir Francis Drake completely missed the San Francisco Bay, but discovered the long crescent bay of Point Reyes in June of 1579, where he hauled The Golden Hinde onto the beach for repairs before striking for the Spice Islands of Indonesia. When he returned to England three years later, Queen Elizabeth I ordered his ships log and journals to be considered as classified information, fearing King Philip of Spain would learn the position of Drake’s “safe harbor”. A hundred years later all of Drake’s records of his circumnavigation, including valuable logs, charts, and artifacts were destroyed forever when the palace containing them burnt to the ground. And so it is that the exact location of Drake’s landing has been hotly debated for a few hundred years. While there are numerous theories of landing sites other than Drake’s Bay, some arguing further up the California coast or Oregon or Washington, most historians think this was the actual bay because of descriptions of the Coast Miwok Indians, the white cliffs, and surprisingly, a particular pocket gopher which inhabits Point Reyes, clearly described in detail by Francis Pretty, a member of Drake’s party.

Drake named the place “Nova Albion”, meaning New England, possibly because of the white cliffs around the bay. Albion, or “the white”, was the Latin name for England and is a reference to the chalky white cliffs of Dover. Drake came here with a single ship, the Golden Hinde, for one of his ships had sunk while attempting to pass through the Straits of Magellan near Cape Horn, and another had to return to England for repairs. The Golden Hinde was carrying various treasures from several encounters with the Spanish on the journey north through South America. While England and Spain were not officially at war, Queen Elizabeth I ordered Drake to harass the Spanish towns and ships along the Pacific coast. Not quite a hundred years had passed since Columbus’ famous discovery, yet the Spanish had been very busy with gold and silver exploits in Peru. Like Henry Morgan in the 17th century, Drake established himself as a daring and successful buccaneer against the Spanish Main and sacked Nombre de Dios on the isthmus of Panama a few years earlier by capturing a mule train laden with silver from Peru. What distinguished Drake as a buccaneer, and not an outright pirate, where the “letters of marque” he carried from the Queen, essentially royal permission to make war on the Spanish whenever convenient. The Spanish galleons were a magnet to enterprising sailors such as Drake and Morgan.

When the Golden Hinde landed in Drake’s Bay, it is likely that she carried Peruvian gold and silver worth over $40M today. This includes 80 pounds of gold and 26 tons of silver taken from the Spanish galleon Cagafuego, Drake’s greatest prize ever, captured off the coast of Ecuador about three months before arriving at Nova Albion.

A few years after Drake, in 1595, Spanish commander Sebastian Rodriguez Cermeno earned the distinction of becoming the first of many documented shipwrecks at Point Reyes. His ship San Augustin was carrying exotic cargo from China to Mexico to be transported across Panama and on to Spain. He anchored in Drake’s Bay and was hit by a winter storm that sent San Augustin up onto the beach where she foundered and broke apart. In Two Years Before the Mast, Richard Henry Dana describes how his vessel in 1838 would always go several miles out to sea when a winter storm was approaching, which was clearly indicated by a southerly. Why Cermeno remained in the bay as the storm approached is a mystery, for the bay is entirely unprotected when a strong breeze kicks up from the south. Nonetheless, the Coast Miwok Indians that inhabited the area must have rejoiced in the bounty they received from the San Augustin, including porcelain from the Ming dynasty. Imagine the head of the tribe replacing his gopher skins with Chinese silks. While the ship and its cargo were lost to Cermeno, he managed to get 70 of his crew into a small open boat and sail for Mexico, reaching Acapulco two months later.

I can’t imagine 70 men in a small boat for two months. Especially with foul tempers following the long cruise from China and the disappointment of their complete loss of ship and cargo. I can imagine a couple of guys in a modern sailboat coming to fisticuffs when one of them continues to whistle an insipid pop tune after an extended weekend. A couple men tired of each other in a cramped sailboat bashing through the waves can be hazard enough, let alone 70.

Unlike me the following morning on my way back to the San Francisco Bay. It was another day of glorious downwind sailing and I was in complete ecstasy. I am hopelessly romantic about my boat, and seeing the clear green ocean waves against Pamela’s forest green hull, the golden sheen of her newly varnished teak, and the brightness of her bronze Dorade vents caused an aching in my heart.

However, the day began cold and foggy, and I managed to rip the top three feet off my mainsail after an accidental gybe. When you are learning to sail, they warn you about a gybe, which is when you are sailing downwind and the wind suddenly catches the mainsail on the wrong side and causes the boom to swing violently to the other side of the boat. They tell you that an uncontrolled gybe can cause the whole rig to come crashing down, or can sweep your crew into the drink in an instant, or both. Many sailors are terrified of the gybe because of this fear imprinted by their sailing instructors. On this day my gybes were necessarily frequent, and gradually more controlled, as Pamela raced downwind in a 22-knot breeze with seas building from flat calm to eight feet as the afternoon progressed.

As the waves began to form white-caps I was fearful not of the gybing, but of the possibility that the mainsail would not hold. Or worse, the torn sail, now in two distinct sections, might get stuck in the track and not come down, which would be a real problem coming back through the Golden Gate. But fair Pamela’s mainsail did indeed hold true in her broad reaching. Even as six-to-eight feet waves pushed hard against her canoe stern and occasionally splashed into the cockpit, she showed her trustworthy sea-kindliness and received the waves with a gentle rocking motion. This is the great advantage of the Crealock 37, a sturdy construction of narrow beam and cut-away keel that holds a course in a boisterous sea and never pounds in the trough of a wave. While Pamela’s hull speed is theoretically capable of going only about six knots, on that day she repeatedly hit over seven knots as she surfed the waves in her downwind course.

At that speed we reached the Golden Gate in only a few hours, unlike the twelve hours it had taken the previous day to reach Drake’s Bay against the wind. There were a few cargo freighters and tugboats lining up in the shipping lane approaching the Gate, and these were to be seriously avoided, for a freighter or a tug in service can not turn to avoid a collision, and if your sailboat is in the way, you’re done and the dream is over. I turned to follow the stern of the first freighter, then made a dash across the shipping lane before the tug entered it, then raced into the entrance to the Gate. Approaching the famous bridge I expected to come to a standstill, since the tide was still ebbing strongly from the bay into the ocean. Yet the remaining ebb tide did not slow Pamela down, nor the severe cross-currents and eddies near the southernmost tower of the bridge. Into the bay she raced. In a small protected area in the lee of the strong wind I gybed her toward the Bay Bridge, and as she emerged from the protected lee she again found her head and raced along past Alcatraz Island. This was probably the fastest sailing I’ve ever done on the bay, and with a howling wind; and yet after spending the previous two days in the ocean it seemed somewhat tame.

A very curious thing happened just in front of the Bay Bridge. Tugging on the jib furling line I attempted to roll in the jib in preparation for taking down her sails. I was really looking forward to the calm waters of South Beach Harbor, and was imaging how great a hot prosciutto pizza and a cold Anchor Steam beer would be. I was able to get the furling line to come in a few feet, but soon I could no longer handle the furler as well as the working jib sheet, for the wind was still strong and pushed hard into the full jib with amazing force. Suddenly I lost control of the jib sheets and they flew out of their blocks and into the air downwind of the boat. Like a maniacal duo of consorting whirling dervishes they twirled together with amazing speed. I watched as they danced violently in space above the water as if hit by a cyclone. The two lines suspended in mid-air foreshadowed the nightmare about falling overboard with the jib sheets streaming out into the breeze. They plopped into the water, and I turned Pamela downwind to reduce the strain on the jib. I was able to quickly furl in the jib and retrieve the sheets from the water. I glanced around nervously to see whether any yachtsmen had witnessed my rookie stunt.

At last I had Pamela back in her slip. The strong winds continued through the evening, and I was glad I was not bashing in the seas beyond the Golden Gate or setting out a second anchor in Drake’s Bay. But I was amazingly proud that I had been in those seas and had managed to pull it off on my first single-handed overnight trip on the ocean.

Anchor Steam is a distinctive brand of dark beer native to San Francisco, utilizing steam in the brewing process and dating back to the days of the California Gold Rush. With my face glowing red from wind and sunburn, my unruly windblown hair standing on end like Einstein’s, and my heart swollen with pride I toasted San Francisco and her Golden Gate. The Anchor Steam never tasted so good.