On December 29, 1810, Charles Fourier sat in his small shop and huddled by the little coal heater in the corner to keep warm. Another winter storm was beginning to blow down the empty back alleys of Paris’ Latin Quarter, and the myriad couples who had so gayly strolled these alleys on Christmas Eve, clutching tightly to each other through their long woolen coats, were no longer here. What were the chances that someone would come to the shop today to purchase his handbook of utopian instructions?

His thoughts were dark on this gray afternoon. In the two years since he had published his first work, The Social Destiny of Man, he had attracted some attention, but very little income as a social scientist. Why should anyone buy his handbook? Anyone could fabricate a story about Paradise.

A garden called Eden, he mused, where everything a man needs is within his grasp, vine-ripened and ready for his plucking. Save for one particular fruit at the dead center of the garden, which the man must never eat.

“There is always that one fruit,” he said aloud. That one thing that brings discomfort even in the very center of Paradise.

One man will find Paradise while sitting under a tree, while another man will study the writings of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle to seek a formula from the ancients. Charles Fourier had read these, and of course Bacon, Spinoza, and Voltaire. Their books were stacked neatly in the corners of his shop, never gathering dust, for he reached for them habitually during his long afternoons of thinking, wondering, and inventing.

And then there was Kant, who reasoned that space and time were not things in themselves, but were formed by our intuitions and perceptions. The lines of Charles Fourier’s mouth turned downward as he tried to make sense of Kant. Like light through a prism that changes its shape and colors depending on the perspective of the eye, the defining characteristics of Paradise change based on the perspective of the viewer.

So Paradise was not really Paradise, but only our perception of Paradise. And that discomfort at the center of Paradise — was that also an invention of our human perception, and if so, couldn’t we simply decide to un-invent it and let it fade from existence?

Charles Fourier’s thoughts were interrupted by a blast of arctic air through the doorway of the petite shop, sending his papers scattering across the dimly lit room like snowflakes ripping down the rue de la Harpe. He clutched in vain at the flying sheets, then resigned himself to the disorder as his good friend Luc bounded into the shop behind the wintry blast.

“Bonjour, mon amie! And how is the business of utopia today?”

“Comme ci, comme ça. Comme d’habitude,” he offered with a trace of a grin, for Luc was always full of energy and his boyish enthusiasm was infectious even in December. “Not many visitors to the shop on such a freezing day, but you know how it is — I must write nonetheless. And how is the boulangerie and the business of baking bread?”

“It is the same each day — the good people of Paris need their daily bread and I am here to pull it fresh from the oven each morning for them. It does not change.” His bright eyes surveyed the little room with the stacks of books in each corner. Luc was not much of a reader, but he knew these books well from his long conversations with Charles Fourier as they strolled the boulevards of nineteenth century Paris on the afternoons when it did not rain or snow.

“It does not change, Luc, but in its constancy and simplicity it forms the essential ingredient of any utopian society.”

Luc laughed easily and grasped his friend by the arm. “Oh Charles, you are such the thinker. Come! Let’s walk to the cafe and warm ourselves with an absinthe, all the better to battle this winter storm.”

They bent their heads to the northerly as they made their way through the labyrinthine streets. “Have you any more news of the Pacific islands reported by Bougainville?” shouted Luc through the wind.

“Oh yes! The reports from the English describe a nation of innocents. They live in the natural realm and seem to be very happy.”

“Is there an apple?” Luc winked.

“Of course, dear Luc. There is always an apple in Paradise.”

“Well continue to study and to write about it, for one day you will be very famous throughout Europe.”

On that freezing winter day Charles Fourier could not know that he would influence many of the greatest philosophers and social scientists who would follow: the likes of Emerson, Thoreau, and Marx. Although Marx would criticize him as being “too utopian.”

Can one be too utopian?

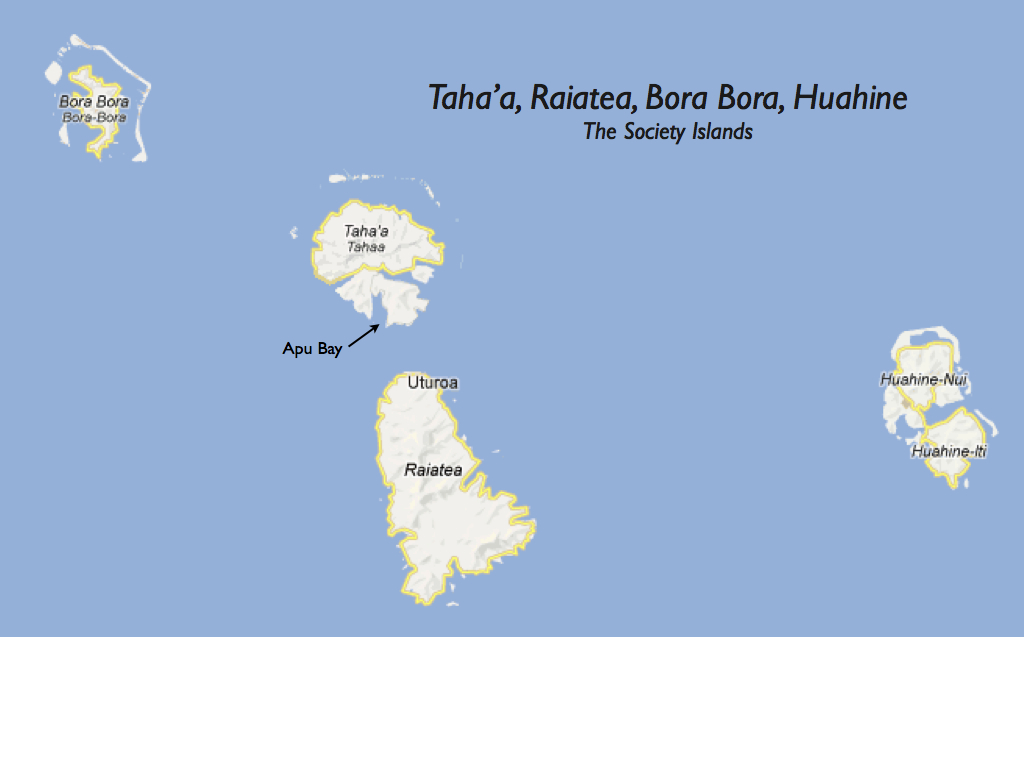

On December 29, 2010, I awoke to a still summer morning in the protected Apu bay of Taha’a on French Polynesia. The sun was beginning to rise on the horizon just viewable across the open lagoon between Taha’a and Raiatea, but its early rays had not yet penetrated the bay itself. Coconut palms grew in a dense fringe along the shore of the bay. The north easterly carried the distinctive scent of vanilla from the lush inland valley. Exactly 200 years after Charles Fourier’s wintry day, I was seeking freshly baked French baguettes in Paradise.

From the transom of my sailboat I stepped into the dinghy without spilling any of the hot sweet coffee that I held tightly in my left hand. I started the outboard with a single pull, then released the lines and motored silently across the little bay, now calm after the squally night. Yesterday the rain had exploded from a cloudburst in the afternoon, and I had stood in the cockpit of the sailboat naked and enjoying the warm shower. The rain had continued in drizzles and squalls throughout the night, and now the day was dawning with only a few clouds with the freshness one feels after a long, warm rinse.

The dinghy glided toward a small pier near the point. I imagined my approach and mentally calculated the deft movements of my right hand on the throttle of the outboard motor, gauging the acceleration and steering direction that would manipulate the prop to bring me alongside the pier without a bump or a scrape.

The day before I had come to the pier with too much speed, and the rubber boat had bounced hard off the pier and flung me sideways, while the motor sputtered out and the wind blew the dinghy back out into the bay. I didn’t want to repeat that performance, and I didn’t want to spill the coffee in my left hand.

Today would be different, I told myself, as each day in Paradise turns out to be. The morning tide was lower now, so the pier stood a little higher in the water. I aimed for the edge of the pier and tried to slow down, but the bow of the dinghy thrust itself under the overhang of the pier.

It was tight fit, just enough to let the bow go under the pier and tight enough to keep it there. The dinghy swung hard alongside while the port gunwhale bumped along under the deck of the pier and took me along with it, bumping and scraping in agitated sympathy. Coffee went everywhere. I fell back feet over head and wrapped myself up in the outboard motor. Oh well, must keep practicing.

At 6:00 a.m. the Taravana Yacht Club bar was empty and there was no one there to enjoy my collision with the pier. Indeed, there would be no one at the bar until I came back later in the afternoon for a pre-sundowner, for it was summer, the off-season for tourism in Tahiti. As if Paradise had an off-season. I secured the dinghy, cleaned up myself, and bailed coffee out of the bilge. As the dinghy rested perfectly alongside the pier I made a plan to perfect that landing by attempting it 10,000 more times in Paradise before The End. It was a good plan.

The Taravana Yacht Club is not really a yacht club. It’s an open-air bar on a little beach at the point of Apu Bay, and Richard the owner lets me tie my boat to a mooring each day if I promise to come to bar each afternoon and have a drink or have his lovely wife Lovina make us poisson cru for dinner.

Richard came to Polynesia from America over thirty years ago sailing a small boat. Like Bernard Moitissier and Paul Gauguin before him, he decided never to leave. He had lots of stories to tell, such as the times he had taken Jimmy Buffet out for sport fishing in the blue water beyond the reef. He now owned the Taravana bar and operated its restaurant with Lovina who is part-French and part-Tahitian and spoke French with me.

I passed through the open bar and out the back door. The dogs in the huts behind were not up yet. They allowed me to pass through the coconut grove and along the hibiscus trail without any sound save the refrain of the song in my head, the chorus of a new song I was composing. In Paradise, you have the space and time to write a song or a story. You don’t have to work very hard to practice your art, for the natural opening of the heart, the mind, and the senses provides you with unlimited space, like an endless sea.

I found the island road and passed the pearl farm. The day before, when I had visited the pearl farm, the elderly madam who lived there told me her husband had passed away the year before. She didn’t know what to do with the pearl farm. She showed me her striking black pearls spread about on tables on her verandah, a verandah which surrounded the house on three sides and offered views of Paradise through the coconut palms as the gentle trades blew a refreshing breeze into the room.

Any true Paradise has pearls, of course; for is Heaven not entered by pearly gates guarded by St. Peter himself?

On the island road I found a coconut that had just fallen from the tree. It was green and ripe, with its husk broken apart by the fall and ready for me to extend my hand for the taking of the sweet coconut meat. From a crack in the center nut I drank up the milky juice. Past the line of banana trees was the small white building, plain and non-descript in itself but exactly as Richard had described to me.

The white building looked like someone’s house, but without windows, and I was a bit shy of approaching. There was no sign on the building. Around the side I found a large open door. Inside were three island men moving racks of dough into a room-sized oven. They had been up since 4:30 a.m. to begin their baking. Each day they prepared bread and sold it to the supermarkets and resorts on Raiatea and Bora Bora.

I gestured for a baguette that had just been taken from the oven and was cooling on a rack. I smiled broadly as one of the men handed me the loaf and took my 50 centimes in his brown hand. He was elderly and serious and did not return my smile, for this was work, and for him the day was no different than the one before or after. In the constancy and simplicity I thought of Charles Fourier.

A younger man spoke English quite well and grinned in a friendly way when I asked him about the round loaves he had just taken from the oven.

“Coconut bread,” he replied.

Voilà — the voluptuous ingredient that makes bread from Paradise unlike no other bread. “Is it sweet?” I wondered.

“Oh yes. We put the meat of the coconut in it.”

“Can I buy one?” I asked him.

He frowned. “I will have to check. They are for a party and we do not normally have them.”

He walked across the narrow island road to a house, then came back a moment later with the wonderful news. “You can have just one.”

“How much is it?”

“It is 200 francs CPF. Be careful. Don’t crush it.”

About two dollars for a fresh-baked circular loaf of coconut bread, crisp and brown on the outside and steamy white inside. I tried to remember the French word for “crush” and couldn’t think of it. I admired the young man’s English which was much better than my French.

“Quelle bonne journée,” I ventured, and with my baguette and coconut loaf under my arm I returned to the grove past the pearl farm and past the dogs who had by now awoken and gave me short barks with half-wagging tails as they admired the aroma of the freshly baked bread. I imagined a day when I would return to Taha’a and stay for more than just a few days, bringing doggie treats for them, and I would teach them to recognize me by the treats accompanied by the special whistle that I always use when feeding my puppy Little Bear.

Through the open bar and out to the pier, where the dinghy waited to humiliate me once again. I maneuvered dexterously from the pier, this time in control even with the baguette, the coffee cup, and the coconut bread which I did not crush. I throttled lightly across the bay and then eased back as I neared the sailboat. I timed the touch of the dinghy’s bow against the swim platform with the gentle swell of the lagoon in the light morning air and set down the coffee cup and the bread upon the platform one-handled while controlling the dinghy, the outboard, and the bow line. A minute vortex in the history of time, in which all good things can happen at once to a man in Paradise.

I heard another outboard motor close by and waved to my neighbors, the young couple I had seen the night before at the Taravana bar, when Richard was explaining to the young lady that the mahi-mahi was basted in shoyu. From the careful way he was explaining this I imagined that the young woman was intolerant to soy, or gluten, or salt. I tried to imagine being intolerant to French cooking in Paradise. It didn’t seem like a happy state.

“Is there any left?” the young man asked me as he gestured at the baguette. My stomach tightened, almost imperceptibly. I imagined the worry of running out of fresh island-baked bread. Of lining up to get while the getting was good, of racing to be at the head of the line. Of economic constraint and the pushing and shoving that accompanies it. The apple emerging once again, turning Paradise suddenly into hell.

As I turned my attention to the tiny sensation in my stomach I realized that by noticing such barely perceptible feelings from within I was making progress in my daily pursuit of mindfulness. “Worry”, I labelled it, and having been labelled it began to fade like a cloud over the lagoon.

I turned to the young man and smiled warmly. “Yes,” I assured him. “There are many and plenty.”